While developing a new project is like rolling on a green field for you, maintaining it is a potential dark twisted nightmare for someone else. Here's a list of guidelines we've found, written and gathered that (we think) works really well with most JavaScript projects here at hive. If you want to share a best practice, or think one of these guidelines should be removed, feel free to share it with us.

- Codebase

- Git

- Documentation

- Environments

- Dependencies

- External Services

- Build & Deploy

- Processes

- Port binding

- Concurrency

- Disposability

- Testing

- Structure and Naming

- Code style

- Logging

- API

- Licensing

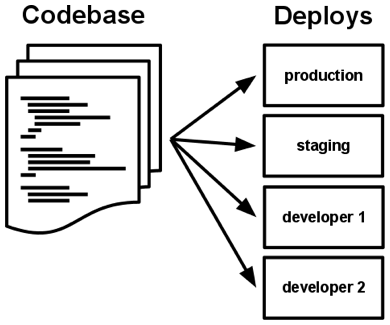

A twelve-factor app is always tracked in a version control system, such as Git, Mercurial, or Subversion. A copy of the revision tracking database is known as a code repository, often shortened to code repo or just repo.

A codebase is any single repo (in a centralized revision control system like Subversion), or any set of repos who share a root commit (in a decentralized revision control system like Git).

There is always a one-to-one correlation between the codebase and the app:

-

If there are multiple codebases, it’s not an app – it’s a distributed system. Each component in a distributed system is an app, and each can individually comply with twelve-factor.

-

Multiple apps sharing the same code is a violation of twelve-factor. The solution here is to factor shared code into libraries which can be included through the dependency manager.

There is only one codebase per app, but there will be many deploys of the app. A deploy is a running instance of the app. This is typically a production site, and one or more staging sites. Additionally, every developer has a copy of the app running in their local development environment, each of which also qualifies as a deploy.

The codebase is the same across all deploys, although different versions may be active in each deploy. For example, a developer has some commits not yet deployed to staging; staging has some commits not yet deployed to production. But they all share the same codebase, thus making them identifiable as different deploys of the same app.

There are a set of rules to keep in mind:

-

Perform work in a feature branch.

Why:

Because this way all work is done in isolation on a dedicated branch rather than the main branch. It allows you to submit multiple pull requests without confusion. You can iterate without polluting the master branch with potentially unstable, unfinished code. read more...

-

Branch out from

developWhy:

This way, you can make sure that code in master will almost always build without problems, and can be mostly used directly for releases (this might be overkill for some projects).

-

Never push into

developormasterbranch. Make a Pull Request.Why:

It notifies team members that they have completed a feature. It also enables easy peer-review of the code and dedicates forum for discussing the proposed feature

-

Update your local

developbranch and do an interactive rebase before pushing your feature and making a Pull RequestWhy:

Rebasing will merge in the requested branch (

masterordevelop) and apply the commits that you have made locally to the top of the history without creating a merge commit (assuming there were no conflicts). Resulting in a nice and clean history. read more ... -

Resolve potential conflicts while rebasing and before making a Pull Request

-

Delete local and remote feature branches after merging.

Why:

It will clutter up your list of branches with dead branches.It insures you only ever merge the branch back into (

masterordevelop) once. Feature branches should only exist while the work is still in progress. -

Before making a Pull Request, make sure your feature branch builds successfully and passes all tests (including code style checks).

Why:

You are about to add your code to a stable branch. If your feature-branch tests fail, there is a high chance that your destination branch build will fail too. Additionally you need to apply code style check before making a Pull Request. It aids readability and reduces the chance of formatting fixes being mingled in with actual changes.

-

Use this .gitignore file.

Why:

It already has a list of system files that should not be sent with your code into a remote repository. In addition, it excludes setting folders and files for most used editors, as well as most common dependency folders.

-

Protect your

developandmasterbranch.Why:

It protects your production-ready branches from receiving unexpected and irreversible changes. read more... Github and Bitbucket

Because of most of the reasons above, we use Feature-branch-workflow with Interactive Rebasing and some elements of Gitflow (naming and having a develop branch). The main steps are as follow:

-

Checkout a new feature/bug-fix branch

git checkout -b <branchname>

-

Make Changes

git add git commit -a

Why:

git commit -awill start an editor which lets you separate the subject from the body. Read more about it in section 1.3. -

Sync with remote to get changes you’ve missed

git checkout develop git pull

Why:

This will give you a chance to deal with conflicts on your machine while rebasing(later) rather than creating a Pull Request that contains conflicts.

-

Update your feature branch with latest changes from develop by interactive rebase

git checkout <branchname> git rebase -i --autosquash develop

Why:

You can use --autosquash to squash all your commits to a single commit. Nobody wants many commits for a single feature in develop branch read more...

-

If you don’t have conflict skip this step. If you have conflicts, resolve them and continue rebase

git add <file1> <file2> ... git rebase --continue

-

Push your branch. Rebase will change history, so you'll have to use

-fto force changes into the remote branch. If someone else is working on your branch, use the less destructive--force-with-lease.git push -f

Why:

When you do a rebase, you are changing the history on your feature branch. As a result, Git will reject normal

git push. Instead, you'll need to use the -f or --force flag. read more... -

Make a Pull Request.

-

Pull request will be accepted, merged and close by a reviewer.

-

Remove your local feature branch if you're done.

git branch -d <branchname>

to remove all branches which are no longer on remote

git fetch -p && for branch in `git branch -vv | grep ': gone]' | awk '{print $1}'`; do git branch -D $branch; done

Having a good guideline for creating commits and sticking to it makes working with Git and collaborating with others a lot easier. Here are some rules of thumb (source):

-

Separate the subject from the body with a newline between the two

Why:

Git is smart enough to distinguish the first line of your commit message as your summary. In fact, if you try git shortlog, instead of git log, you will see a long list of commit messages, consisting of the id of the commit, and the summary only

-

Limit the subject line to 50 characters and Wrap the body at 72 characters

why

Commits should be as fine-grained and focused as possible, it is not the place to be verbose. read more...

-

Capitalize the subject line

-

Do not end the subject line with a period

-

Use imperative mood in the subject line

Why:

Rather than writing messages that say what a committer has done. It's better to consider these messages as the instructions for what is going to be done after the commit is applied on the repository. read more...

-

Use the body to explain what and why as opposed to how

- Use this template for

README.md, Feel free to add uncovered sections. - For projects with more than one repository, provide links to them in their respective

README.mdfiles. - Keep

README.mdupdated as a project evolves. - Comment your code. Try to make it as clear as possible what you are intending with each major section.

- If there is an open discussion on github or stackoverflow about the code or approach you're using, include the link in your comment,

- Don't use comments as an excuse for a bad code. Keep your code clean.

- Don't use clean code as an excuse to not comment at all.

- Keep comments relevant as your code evolves.

-

Define separate

development,testandproductionenvironments if needed.Why:

Different data, tokens, APIs, ports etc... might be needed on different environments. You may want an isolated

developmentmode that calls fake API which returns predictable data, making both automated and manually testing much easier. Or you may want to enable Google Analytics only onproductionand so on. read more... -

Load your deployment specific configurations from environment variables and never add them to the codebase as constants, look at this sample.

Why:

You have tokens, passwords and other valuable information in there. Your config should be correctly separated from the app internals as if the codebase could be made public at any moment.

How:

Use

.envfiles to store your variables and add them to.gitignoreto be excluded. Instead, commit a.env.examplewhich serves as a guide for developers. For production, you should still set your environment variables in the standard way. read more -

It’s recommended to validate environment variables before your app starts. Look at this sample using

joito validate provided values.Why:

It may save others from hours of troubleshooting.

-

Set your node version in

enginesinpackage.jsonWhy:

It lets others know the version of node the project works on. read more...

-

Additionally, use

nvmand create a.nvmrcin your project root. Don't forget to mention it in the documentationWhy:

Any one who uses

nvmcan simply usenvm useto switch to the suitable node version. read more... -

It's a good idea to setup a

preinstallscript that checks node and npm versionsWhy:

Some dependencies may fail when installed by newer versions of npm.

-

Use Docker image if you can.

Why:

It can give you a consistent environment across the entire workflow. Without much need to fiddle with dependencies or configs. read more...

-

Use local modules instead of using globally installed modules

Why:

Lets you share your tooling with your colleague instead of expecting them to have it globally on their systems.

-

Make sure your team members get the exact same dependencies as you

Why:

Because you want the code to behave as expected and identical in any development machine read more...

how:

Use

package-lock.jsononnpm@5or higherI don't have npm@5:

Alternatively you can use

Yarnand make sure to mention it inREADME.md. Your lock file andpackage.jsonshould have the same versions after each dependency update. read more...I don't like the name

Yarn:Too bad. For older versions of

npm, use—save --save-exactwhen installing a new dependency and createnpm-shrinkwrap.jsonbefore publishing. read more...

An app’s config is everything that is likely to vary between deploys (staging, production, developer environments, etc). This includes:

- Resource handles to the database, Memcached, and other backing services

- Credentials to external services such as Amazon S3 or Twitter

- Per-deploy values such as the canonical hostname for the deploy

Apps sometimes store config as constants in the code. This is a violation of twelve-factor, which requires strict separation of config from code. Config varies substantially across deploys, code does not.

A litmus test for whether an app has all config correctly factored out of the code is whether the codebase could be made open source at any moment, without compromising any credentials.

Note that this definition of “config” does not include internal application config, such as config/routes.rb in Rails, urls.py in Python/Django, or how code modules are connected in Spring. This type of config does not vary between deploys, and so is best done in the code.

Another approach to config is the use of config files which are not checked into revision control, such as config/database.yml in Rails. This is a huge improvement over using constants which are checked into the code repo, but still has weaknesses: it’s easy to mistakenly check in a config file to the repo; there is a tendency for config files to be scattered about in different places and different formats, making it hard to see and manage all the config in one place. Further, these formats tend to be language- or framework-specific.

The twelve-factor app stores config in environment variables (often shortened to env vars or env). Env vars are easy to change between deploys without changing any code; unlike config files, there is little chance of them being checked into the code repo accidentally; and unlike custom config files, or other config mechanisms such as Java System Properties, they are a language- and OS-agnostic standard.

Another aspect of config management is grouping. Sometimes apps batch config into named groups (often called “environments”) named after specific deploys, such as the development, test, and production environments in Rails. This method does not scale cleanly: as more deploys of the app are created, new environment names are necessary, such as staging or qa. As the project grows further, developers may add their own special environments like joes-staging, resulting in a combinatorial explosion of config which makes managing deploys of the app very brittle.

In a twelve-factor app, env vars are granular controls, each fully orthogonal to other env vars. They are never grouped together as “environments”, but instead are independently managed for each deploy. This is a model that scales up smoothly as the app naturally expands into more deploys over its lifetime.

Most programming languages offer a packaging system for distributing support libraries, such as CPAN for Perl or Rubygems for Ruby. Libraries installed through a packaging system can be installed system-wide (known as “site packages”) or scoped into the directory containing the app (known as “vendoring” or “bundling”).

A twelve-factor app never relies on implicit existence of system-wide packages. It declares all dependencies, completely and exactly, via a dependency declaration manifest. Furthermore, it uses a dependency isolation tool during execution to ensure that no implicit dependencies “leak in” from the surrounding system. The full and explicit dependency specification is applied uniformly to both production and development.

For example, Bundler for Ruby offers the Gemfile manifest format for dependency declaration and bundle exec for dependency isolation. In Python there are two separate tools for these steps – Pip is used for declaration and Virtualenv for isolation. Even C has Autoconf for dependency declaration, and static linking can provide dependency isolation. No matter what the toolchain, dependency declaration and isolation must always be used together – only one or the other is not sufficient to satisfy twelve-factor.

One benefit of explicit dependency declaration is that it simplifies setup for developers new to the app. The new developer can check out the app’s codebase onto their development machine, requiring only the language runtime and dependency manager installed as prerequisites. They will be able to set up everything needed to run the app’s code with a deterministic build command. For example, the build command for Ruby/Bundler is bundle install, while for Clojure/Leiningen it is lein deps.

Twelve-factor apps also do not rely on the implicit existence of any system tools. Examples include shelling out to ImageMagick or curl. While these tools may exist on many or even most systems, there is no guarantee that they will exist on all systems where the app may run in the future, or whether the version found on a future system will be compatible with the app. If the app needs to shell out to a system tool, that tool should be vendored into the app.

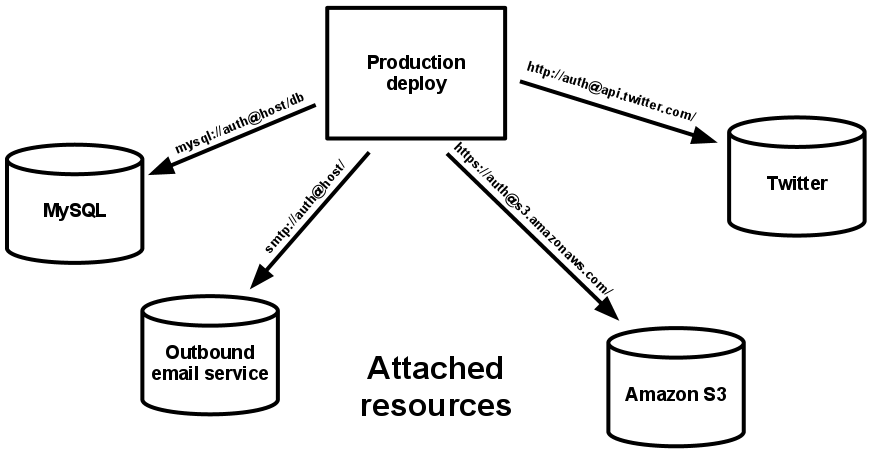

A backing service is any service the app consumes over the network as part of its normal operation. Examples include datastores (such as MySQL or CouchDB), messaging/queueing systems (such as RabbitMQ or Beanstalkd), SMTP services for outbound email (such as Postfix), and caching systems (such as Memcached).

Backing services like the database are traditionally managed by the same systems administrators as the app’s runtime deploy. In addition to these locally-managed services, the app may also have services provided and managed by third parties. Examples include SMTP services (such as Postmark), metrics-gathering services (such as New Relic or Loggly), binary asset services (such as Amazon S3), and even API-accessible consumer services (such as Twitter, Google Maps, or Last.fm).

The code for a twelve-factor app makes no distinction between local and third party services. To the app, both are attached resources, accessed via a URL or other locator/credentials stored in the config. A deploy of the twelve-factor app should be able to swap out a local MySQL database with one managed by a third party (such as Amazon RDS) without any changes to the app’s code. Likewise, a local SMTP server could be swapped with a third-party SMTP service (such as Postmark) without code changes. In both cases, only the resource handle in the config needs to change.

Each distinct backing service is a resource. For example, a MySQL database is a resource; two MySQL databases (used for sharding at the application layer) qualify as two distinct resources. The twelve-factor app treats these databases as attached resources, which indicates their loose coupling to the deploy they are attached to.

Resources can be attached and detached to deploys at will. For example, if the app’s database is misbehaving due to a hardware issue, the app’s administrator might spin up a new database server restored from a recent backup. The current production database could be detached, and the new database attached – all without any code changes.

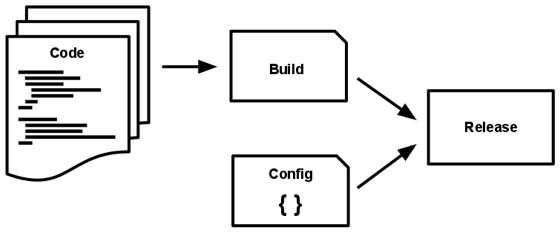

A codebase is transformed into a (non-development) deploy through three stages:

- The build stage is a transform which converts a code repo into an executable bundle known as a build. Using a version of the code at a commit specified by the deployment process, the build stage fetches vendors dependencies and compiles binaries and assets.

- The release stage takes the build produced by the build stage and combines it with the deploy’s current config. The resulting release contains both the build and the config and is ready for immediate execution in the execution environment.

- The run stage (also known as “runtime”) runs the app in the execution environment, by launching some set of the app’s processes against a selected release.

Code becomes a build, which is combined with config to create a release.

The twelve-factor app uses strict separation between the build, release, and run stages. For example, it is impossible to make changes to the code at runtime, since there is no way to propagate those changes back to the build stage.

Deployment tools typically offer release management tools, most notably the ability to roll back to a previous release. For example, the Capistrano deployment tool stores releases in a subdirectory named releases, where the current release is a symlink to the current release directory. Its rollback command makes it easy to quickly roll back to a previous release.

Every release should always have a unique release ID, such as a timestamp of the release (such as 2011-04-06-20:32:17) or an incrementing number (such as v100). Releases are an append-only ledger and a release cannot be mutated once it is created. Any change must create a new release.

Builds are initiated by the app’s developers whenever new code is deployed. Runtime execution, by contrast, can happen automatically in cases such as a server reboot, or a crashed process being restarted by the process manager. Therefore, the run stage should be kept to as few moving parts as possible, since problems that prevent an app from running can cause it to break in the middle of the night when no developers are on hand. The build stage can be more complex, since errors are always in the foreground for a developer who is driving the deploy.

The app is executed in the execution environment as one or more processes.

In the simplest case, the code is a stand-alone script, the execution environment is a developer’s local laptop with an installed language runtime, and the process is launched via the command line (for example, python my_script.py). On the other end of the spectrum, a production deploy of a sophisticated app may use many process types, instantiated into zero or more running processes.

Twelve-factor processes are stateless and share-nothing. Any data that needs to persist must be stored in a stateful backing service, typically a database.

The memory space or filesystem of the process can be used as a brief, single-transaction cache. For example, downloading a large file, operating on it, and storing the results of the operation in the database. The twelve-factor app never assumes that anything cached in memory or on disk will be available on a future request or job – with many processes of each type running, chances are high that a future request will be served by a different process. Even when running only one process, a restart (triggered by code deploy, config change, or the execution environment relocating the process to a different physical location) will usually wipe out all local (e.g., memory and filesystem) state.

Asset packagers (such as Jammit or django-compressor) use the filesystem as a cache for compiled assets. A twelve-factor app prefers to do this compiling during the build stage, such as the Rails asset pipeline, rather than at runtime.

Some web systems rely on “sticky sessions” – that is, caching user session data in memory of the app’s process and expecting future requests from the same visitor to be routed to the same process. Sticky sessions are a violation of twelve-factor and should never be used or relied upon. Session state data is a good candidate for a datastore that offers time-expiration, such as Memcached or Redis.

Web apps are sometimes executed inside a webserver container. For example, PHP apps might run as a module inside Apache HTTPD, or Java apps might run inside Tomcat.

The twelve-factor app is completely self-contained and does not rely on runtime injection of a webserver into the execution environment to create a web-facing service. The web app exports HTTP as a service by binding to a port, and listening to requests coming in on that port.

In a local development environment, the developer visits a service URL like http://localhost:5000/ to access the service exported by their app. In deployment, a routing layer handles routing requests from a public-facing hostname to the port-bound web processes.

This is typically implemented by using dependency declaration to add a webserver library to the app, such as Tornado for Python, Thin for Ruby, or Jetty for Java and other JVM-based languages. This happens entirely in user space, that is, within the app’s code. The contract with the execution environment is binding to a port to serve requests.

HTTP is not the only service that can be exported by port binding. Nearly any kind of server software can be run via a process binding to a port and awaiting incoming requests. Examples include ejabberd (speaking XMPP), and Redis (speaking the Redis protocol).

Note also that the port-binding approach means that one app can become the backing service for another app, by providing the URL to the backing app as a resource handle in the config for the consuming app.

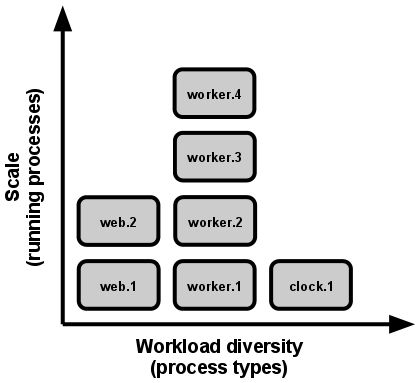

Any computer program, once run, is represented by one or more processes. Web apps have taken a variety of process-execution forms. For example, PHP processes run as child processes of Apache, started on demand as needed by request volume. Java processes take the opposite approach, with the JVM providing one massive uberprocess that reserves a large block of system resources (CPU and memory) on startup, with concurrency managed internally via threads. In both cases, the running process(es) are only minimally visible to the developers of the app.

Scale is expressed as running processes, workload diversity is expressed as process types.

**In the twelve-factor app, processes are a first class citizen.** Processes in the twelve-factor app take strong cues from [the unix process model for running service daemons](https://adam.herokuapp.com/past/2011/5/9/applying_the_unix_process_model_to_web_apps/). Using this model, the developer can architect their app to handle diverse workloads by assigning each type of work to a process type. For example, HTTP requests may be handled by a web process, and long-running background tasks handled by a worker process.This does not exclude individual processes from handling their own internal multiplexing, via threads inside the runtime VM, or the async/evented model found in tools such as EventMachine, Twisted, or Node.js. But an individual VM can only grow so large (vertical scale), so the application must also be able to span multiple processes running on multiple physical machines.

The process model truly shines when it comes time to scale out. The share-nothing, horizontally partitionable nature of twelve-factor app processes means that adding more concurrency is a simple and reliable operation. The array of process types and number of processes of each type is known as the process formation.

Twelve-factor app processes should never daemonize or write PID files. Instead, rely on the operating system’s process manager (such as Upstart, a distributed process manager on a cloud platform, or a tool like Foreman in development) to manage output streams, respond to crashed processes, and handle user-initiated restarts and shutdowns.

The twelve-factor app’s processes are disposable, meaning they can be started or stopped at a moment’s notice. This facilitates fast elastic scaling, rapid deployment of code or config changes, and robustness of production deploys.

Processes should strive to minimize startup time. Ideally, a process takes a few seconds from the time the launch command is executed until the process is up and ready to receive requests or jobs. Short startup time provides more agility for the release process and scaling up; and it aids robustness, because the process manager can more easily move processes to new physical machines when warranted.

Processes shut down gracefully when they receive a SIGTERM signal from the process manager. For a web process, graceful shutdown is achieved by ceasing to listen on the service port (thereby refusing any new requests), allowing any current requests to finish, and then exiting. Implicit in this model is that HTTP requests are short (no more than a few seconds), or in the case of long polling, the client should seamlessly attempt to reconnect when the connection is lost.

For a worker process, graceful shutdown is achieved by returning the current job to the work queue. For example, on RabbitMQ the worker can send a NACK; on Beanstalkd, the job is returned to the queue automatically whenever a worker disconnects. Lock-based systems such as Delayed Job need to be sure to release their lock on the job record. Implicit in this model is that all jobs are reentrant, which typically is achieved by wrapping the results in a transaction, or making the operation idempotent.

Processes should also be robust against sudden death, in the case of a failure in the underlying hardware. While this is a much less common occurrence than a graceful shutdown with SIGTERM, it can still happen. A recommended approach is use of a robust queueing backend, such as Beanstalkd, that returns jobs to the queue when clients disconnect or time out. Either way, a twelve-factor app is architected to handle unexpected, non-graceful terminations. Crash-only design takes this concept to its logical conclusion.

-

Have a

testmode environment if needed.Why:

While sometimes end to end testing in

productionmode might seem enough, there are some exceptions: One example is you may not want to enable analytical information on a 'production' mode and pollute someone's dashboard with test data. The other example is that your API may have rate limits inproductionand blocks your test calls after a certain amount of requests. -

Place your test files next to the tested modules using

*.test.jsor*.spec.jsnaming convention, likemoduleName.spec.jsWhy:

You don't want to dig through a folder structure to find a unit test. read more...

-

Put your additional test files into a separate test folder to avoid confusion.

Why:

Some test files don't particularly relate to any specific implementation file. You have to put it in a folder that is most likely to be found by other developers:

__test__folder. This name:__test__is also standard now and gets picked up by most JavaScript testing frameworks. -

Write testable code, avoid side effects, extract side effects, write pure functions

Why:

You want to test a business logic as separate units. You have to "minimize the impact of randomness and nondeterministic processes on the reliability of your code". read more...

A pure function is a function that always returns the same output for the same input. Conversely, an impure function is one that may have side effects or depends on conditions from the outside to produce a value. That makes it less predictable read more...

-

Use a static type checker

Why:

Sometimes you may need a Static type checker. It brings a certain level of reliability to your code. read more...

-

Run tests locally before making any pull requests to

develop.Why:

You don't want to be the one who caused production-ready branch build to fail. Run your tests after your

rebaseand before pushing your feature-branch to a remote repository. -

Document your tests including instructions in the relevant section of your

README.mdfile.Why:

It's a handy note you leave behind for other developers or DevOps experts or QA or anyone who gets lucky enough to work on your code.

-

Organize your files around product features / pages / components, not roles. Also, place your test files next to their implementation.

Bad

. ├── controllers | ├── product.js | └── user.js ├── models | ├── product.js | └── user.jsGood

. ├── product | ├── index.js | ├── product.js | └── product.test.js ├── user | ├── index.js | ├── user.js | └── user.test.jsWhy:

Instead of a long list of files, you will create small modules that encapsulate one responsibility including its test and so on. It gets much easier to navigate through and things can be found at a glance.

-

Put your additional test files to a separate test folder to avoid confusion.

Why:

It is a time saver for other developers or DevOps experts in your team.

-

Use a

./configfolder and don't make different config files for different environments.Why:

When you break down a config file for different purposes (database, API and so on); putting them in a folder with a very recognizable name such as

configmakes sense. Just remember not to make different config files for different environments. It doesn't scale cleanly, as more deploys of the app are created, new environment names are necessary. Values to be used in config files should be provided by environment variables. read more... -

Put your scripts in a

./scriptsfolder. This includesbashandnodescripts.Why:

It's very likely you may end up with more than one script, production build, development build, database feeders, database synchronization and so on.

-

Place your build output in a

./buildfolder. Addbuild/to.gitignore.Why:

Name it what you like,

distis also cool. But make sure that keep it consistent with your team. What gets in there is most likely generated (bundled, compiled, transpiled) or moved there. What you can generate, your teammates should be able to generate too, so there is no point committing them into your remote repository. Unless you specifically want to. -

Use

PascalCase' 'camelCasefor filenames and directory names. UsePascalCaseonly for Components. -

CheckBox/index.jsshould have theCheckBoxcomponent, as couldCheckBox.js, but notCheckBox/CheckBox.jsorcheckbox/CheckBox.jswhich are redundant. -

Ideally the directory name should match the name of the default export of

index.js.Why:

Then you can expect what component or module you will receive by simply just importing its parent folder.

-

Use stage-2 and higher JavaScript (modern) syntax for new projects. For old project stay consistent with existing syntax unless you intend to modernise the project.

Why:

This is all up to you. We use transpilers to use advantages of new syntax. stage-2 is more likely to eventually become part of the spec with only minor revisions.

-

Include code style check in your build process.

Why:

Breaking your build is one way of enforcing code style to your code. It prevents you from taking it less seriously. Do it for both client and server-side code. read more...

-

Use ESLint - Pluggable JavaScript linter to enforce code style.

Why:

We simply prefer

eslint, you don't have to. It has more rules supported, the ability to configure the rules, and ability to add custom rules. -

We use Airbnb JavaScript Style Guide for JavaScript, Read more. Use the javascript style guide required by the project or your team.

-

We use Flow type style check rules for ESLint. when using FlowType.

Why:

Flow introduces few syntaxes that also need to follow certain code style and be checked.

-

Use

.eslintignoreto exclude file or folders from code style check.Why:

You don't have to pollute your code with

eslint-disablecomments whenever you need to exclude a couple of files from style checking. -

Remove any of your

eslintdisable comments before making a Pull Request.Why:

It's normal to disable style check while working on a code block to focus more on the logic. Just remember to remove those

eslint-disablecomments and follow the rules. -

Depending on the size of the task use

//TODO:comments or open a ticket.Why:

So then you can remind yourself and others about a small task (like refactoring a function, or updating a comment). For larger tasks use

//TODO(#3456)which is enforced by a lint rule and the number is an open ticket. -

Always comment and keep them relevant as code changes. Remove commented blocks of code.

Why:

Your code should be as readable as possible, you should get rid of anything distracting. If you refactored a function, don't just comment out the old one, remove it.

-

Avoid irrelevant or funny comments, logs or naming.

Why:

While your build process may(should) get rid of them, sometimes your source code may get handed over to another company/client and they may not share the same banter.

-

Make your names search-able with meaningful distinctions avoid shortened names. For functions Use long, descriptive names. A function name should be a verb or a verb phrase, and it needs to communicate its intention.

Why:

It makes it more natural to read the source code.

-

Organize your functions in a file according to the step-down rule. Higher level functions should be on top and lower levels below.

Why:

It makes it more natural to read the source code.

-

Avoid client-side console logs in production

Why:

Even though your build process can(should) get rid of them, but make sure your code style check gives your warning about console logs.

-

Produce readable production logging. Ideally use logging libraries to be used in production mode (such as winston or node-bunyan).

Why:

It makes your troubleshooting less unpleasant with colorization, timestamps, log to a file in addition to the console or even logging to a file that rotates daily. read more...

Why:

Because we try to enforce development of sanely constructed RESTful interfaces, which team members and clients can consume simply and consistently.

Why:

Lack of consistency and simplicity can massively increase integration and maintenance costs. Which is why

API designis included in this document.

-

We mostly follow resource-oriented design. It has three main factors: resources, collection, and URLs.

- A resource has data, gets nested, and there are methods that operate against it

- A group of resources is called a collection.

- URL identifies the online location of resource or collection.

Why:

This is a very well-known design to developers (your main API consumers). Apart from readability and ease of use, it allows us to write generic libraries and connectors without even knowing what the API is about.

-

use kebab-case for URLs.

-

use camelCase for parameters in the query string or resource fields.

-

use plural kebab-case for resource names in URLs.

-

Always use a plural nouns for naming a url pointing to a collection:

/users.Why:

Basically, it reads better and keeps URLs consistent. read more...

-

In the source code convert plurals to variables and properties with a List suffix.

Why:

Plural is nice in the URL but in the source code, it’s just too subtle and error-prone.

-

Always use a singular concept that starts with a collection and ends to an identifier:

/students/245743 /airports/kjfk -

Avoid URLs like this:

GET /blogs/:blogId/posts/:postId/summaryWhy:

This is not pointing to a resource but to a property instead. You can pass the property as a parameter to trim your response.

-

Keep verbs out of your resource URLs.

Why:

Because if you use a verb for each resource operation you soon will have a huge list of URLs and no consistent pattern which makes it difficult for developers to learn. Plus we use verbs for something else

-

Use verbs for non-resources. In this case, your API doesn't return any resources. Instead, you execute an operation and return the result. These are not CRUD (create, retrieve, update, and delete) operations:

/translate?text=HalloWhy:

Because for CRUD we use HTTP methods on

resourceorcollectionURLs. The verbs we were talking about are actuallyControllers. You usually don't develop many of these. read more... -

The request body or response type is JSON then please follow

camelCaseforJSONproperty names to maintain the consistency.Why:

This is a JavaScript project guideline, Where Programming language for generating JSON as well as Programming language for parsing JSON are assumed to be JavaScript.

-

Even though a resource is a singular concept that is similar to an object instance or database record, you should not use your

table_namefor a resource name andcolumn_nameresource property.Why:

Because your intention is to expose Resources, not your database schema details

-

Again, only use nouns in your URL when naming your resources and don’t try to explain their functionality.

Why:

Only use nouns in your resource URLs, avoid endpoints like

/addNewUseror/updateUser. Also avoid sending resource operations as a parameter. -

Explain the CRUD functionalities using HTTP methods:

How:

GET: To retrieve a representation of a resource.POST: To create new resources and sub-resourcesPUT: To update existing resourcesPATCH: To update existing resources. It only updates the fields that were supplied, leaving the others aloneDELETE: To delete existing resources -

For nested resources, use the relation between them in the URL. For instance, using

idto relate an employee to a company.Why:

This is a natural way to make resources explorable.

How:

GET /schools/2/students, should get the list of all students from school 2GET /schools/2/students/31, should get the details of student 31, which belongs to school 2DELETE /schools/2/students/31, should delete student 31, which belongs to school 2PUT /schools/2/students/31, should update info of student 31, Use PUT on resource-URL only, not collectionPOST /schools, should create a new school and return the details of the new school created. Use POST on collection-URLs -

Use a simple ordinal number for a version with a

vprefix (v1, v2). Move it all the way to the left in the URL so that it has the highest scope:http://api.domain.com/v1/schools/3/studentsWhy:

When your APIs are public for other third parties, upgrading the APIs with some breaking change would also lead to breaking the existing products or services using your APIs. Using versions in your URL can prevent that from happening. read more...

-

Response messages must be self-descriptive. A good error message response might look something like this:

{ "code": 1234, "message" : "Something bad happened", "description" : "More details" }or for validation errors:

{ "code" : 2314, "message" : "Validation Failed", "errors" : [ { "code" : 1233, "field" : "email", "message" : "Invalid email" }, { "code" : 1234, "field" : "password", "message" : "No password provided" } ] }Why:

developers depend on well-designed errors at the critical times when they are troubleshooting and resolving issues after the applications they've built using your APIs are in the hands of their users.

Note: Keep security exception messages as generic as possible. For instance, Instead of saying ‘incorrect password’, you can reply back saying ‘invalid username or password’ so that we don’t unknowingly inform user that username was indeed correct and only the password was incorrect.

-

Use only these 8 status codes to send with you response to describe whether everything worked, The client app did something wrong or The API did something wrong.

Which ones:

200 OKresponse represents success forGET,PUTorPOSTrequests.201 Createdfor when new instance is created. Creating a new instance, usingPOSTmethod returns201status code.304 Not Modifiedresponse is to minimize information transfer when the recipient already has cached representations400 Bad Requestfor when the request was not processed, as the server could not understand what the client is asking for401 Unauthorizedfor when the request lacks valid credentials and it should re-request with the required credentials.403 Forbiddenmeans the server understood the request but refuses to authorize it.404 Not Foundindicates that the requested resource was not found.500 Internal Server Errorindicates that the request is valid, but the server could not fulfill it due to some unexpected condition.Why:

Most API providers use a small subset HTTP status codes. For example, the Google GData API uses only 10 status codes, Netflix uses 9, and Digg, only 8. Of course, these responses contain a body with additional information.There are over 70 HTTP status codes. However, most developers don't have all 70 memorized. So if you choose status codes that are not very common you will force application developers away from building their apps and over to wikipedia to figure out what you're trying to tell them. read more...

-

Provide total numbers of resources in your response

-

Accept

limitandoffsetparameters -

The amount of data the resource exposes should also be taken into account. The API consumer doesn't always need the full representation of a resource.Use a fields query parameter that takes a comma separated list of fields to include:

GET /student?fields=id,name,age,class -

Pagination, filtering, and sorting don’t need to be supported from start for all resources. Document those resources that offer filtering and sorting.

These are some basic security best practices:

-

Don't use basic authentication. Authentication tokens must not be transmitted in the URL:

GET /users/123?token=asdf....Why:

Because Token, or user ID and password are passed over the network as clear text (it is base64 encoded, but base64 is a reversible encoding), the basic authentication scheme is not secure. read more...

-

Tokens must be transmitted using the Authorization header on every request:

Authorization: Bearer xxxxxx, Extra yyyyy -

Authorization Code should be short-lived.

-

Reject any non-TLS requests by not responding to any HTTP request to avoid any insecure data exchange. Respond to HTTP requests by

403 Forbidden. -

Consider using Rate Limiting

Why:

To protect your APIs from bot threats that call your API thousands of times per hour. You should consider implementing rate limit early on.

-

Setting HTTP headers appropriately can help to lock down and secure your web application. read more...

-

Your API should convert the received data to their canonical form or reject them. Return 400 Bad Request with details about any errors from bad or missing data.

-

All the data exchanged with the ReST API must be validated by the API.

-

Serialize your JSON

Why:

A key concern with JSON encoders is preventing arbitrary JavaScript remote code execution within the browser... or, if you're using node.js, on the server. It's vital that you use a proper JSON serializer to encode user-supplied data properly to prevent the execution of user-supplied input on the browser.

-

Validate the content-type and mostly use

application/*json(Content-Type header).Why:

For instance, accepting the

application/x-www-form-urlencodedmime type allows the attacker to create a form and trigger a simple POST request. The server should never assume the Content-Type. A lack of Content-Type header or an unexpected Content-Type header should result in the server rejecting the content with a4XXresponse.

- Fill the

API Referencesection in README.md template for API. - Describe API authentication methods with a code sample

- Explaining The URL Structure (path only, no root URL) including The request type (Method)

For each endpoint explain:

-

URL Params If URL Params exist, specify them in accordance with name mentioned in URL section:

Required: id=[integer] Optional: photo_id=[alphanumeric] -

If the request type is POST, provide working examples. URL Params rules apply here too. Separate the section into Optional and Required.

-

Success Response, What should be the status code and is there any return data? This is useful when people need to know what their callbacks should expect:

Code: 200 Content: { id : 12 } -

Error Response, Most endpoints have many ways to fail. From unauthorized access to wrongful parameters etc. All of those should be listed here. It might seem repetitive, but it helps prevent assumptions from being made. For example

{ "code": 403, "message" : "Authentication failed", "description" : "Invalid username or password" } -

Use API design tools, There are lots of open source tools for good documentation such as API Blueprint and Swagger.

Make sure you use resources that you have the rights to use. If you use libraries, remember to look for MIT, Apache or BSD but if you modify them, then take a look into license details. Copyrighted images and videos may cause legal problems.

Sources: 12Factor, RisingStack Engineering, Mozilla Developer Network, Heroku Dev Center, Airbnb/javascript, Atlassian Git tutorials, Apigee, Wishtack